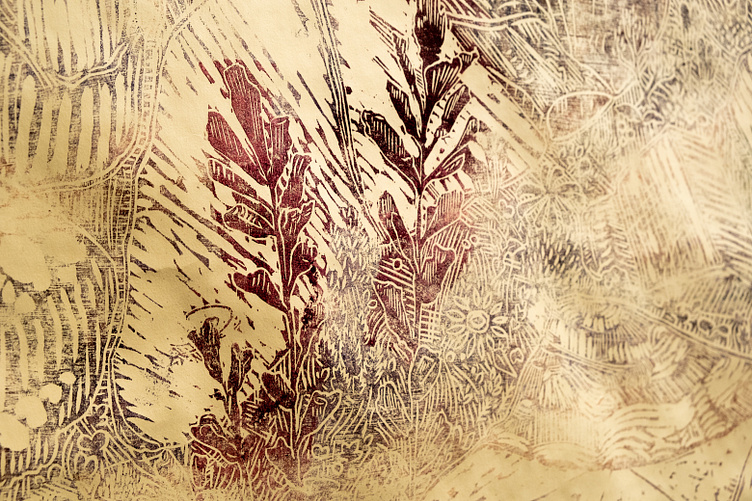

The Burren

Woodblock print series exploring how landscapes change from human activity. (1.22m² / 4ft², oil-based ink, hand printed)

Background

Ireland’s landscape, once one of the most heavily forested in Europe, has never recovered from deforestation under Norman and English conquest. Its tree bare hills show the remains of the Celtic settlements that were depopulated by occupation, and earthen mounds (known as ráths in Gaelic) that surrounded villages and chief’s houses still hold a kind of magic - “fairy rings” seen as verdant circles across the countryside.

•

Trees were venerated by Irish Celts as a source of spirituality and power. They were used as medicine and associated with warding away bad spirits and bringing good luck. In the ancient legal code of Ireland, called the Brehon laws, trees were considered communal property and cutting or mutilating them was a serious offense.

The first major period of deforestation followed the Norman conquest of 1161, but loss of woodland accelerated when Ireland became a British colony in the 16th century. Systematic wood-clearing subdued the Irish, who were dependent on forests for shelter and ambush. In the 17th-century, plantations, which had started in the southern Midlands, spread through the entire country, converting 1.5 of the 2 million acres of Irish landscape into farmland. The loss of woodland had a tremendously negative effect on both the Irish, who were separated from their culture by the new land-exploiting system, as well as on Ireland’s biodiversity; wolves, eagles, and wild cats went extinct.

Nature, which had remained a source of livelihood and spirituality for centuries, had gradually become an awe-inspiring, threatening presence. In the 18th century, reforestation efforts were devised by the direct descendants of the planters. The Irish, who already regarded landowners as foreigners, became more hostile towards both the owners and the land, mutilating and cutting trees as a sign of political protest. This reforestation continued until 1845, despite famine-stricken farmers who worked under the landowners being denied all sources of income. Ultimately, funneling resources out of Ireland resulted in an Gorta Mór, the Great Irish Famine - killing more than one million people and forcing the emigration of another million from 1845 to 1852.

The 20th century held the fight for independence from Britain, civil war, urban growth, the world wars, and increased tourism.

The Irish landscape, though there have been efforts to reforest, has never recovered.